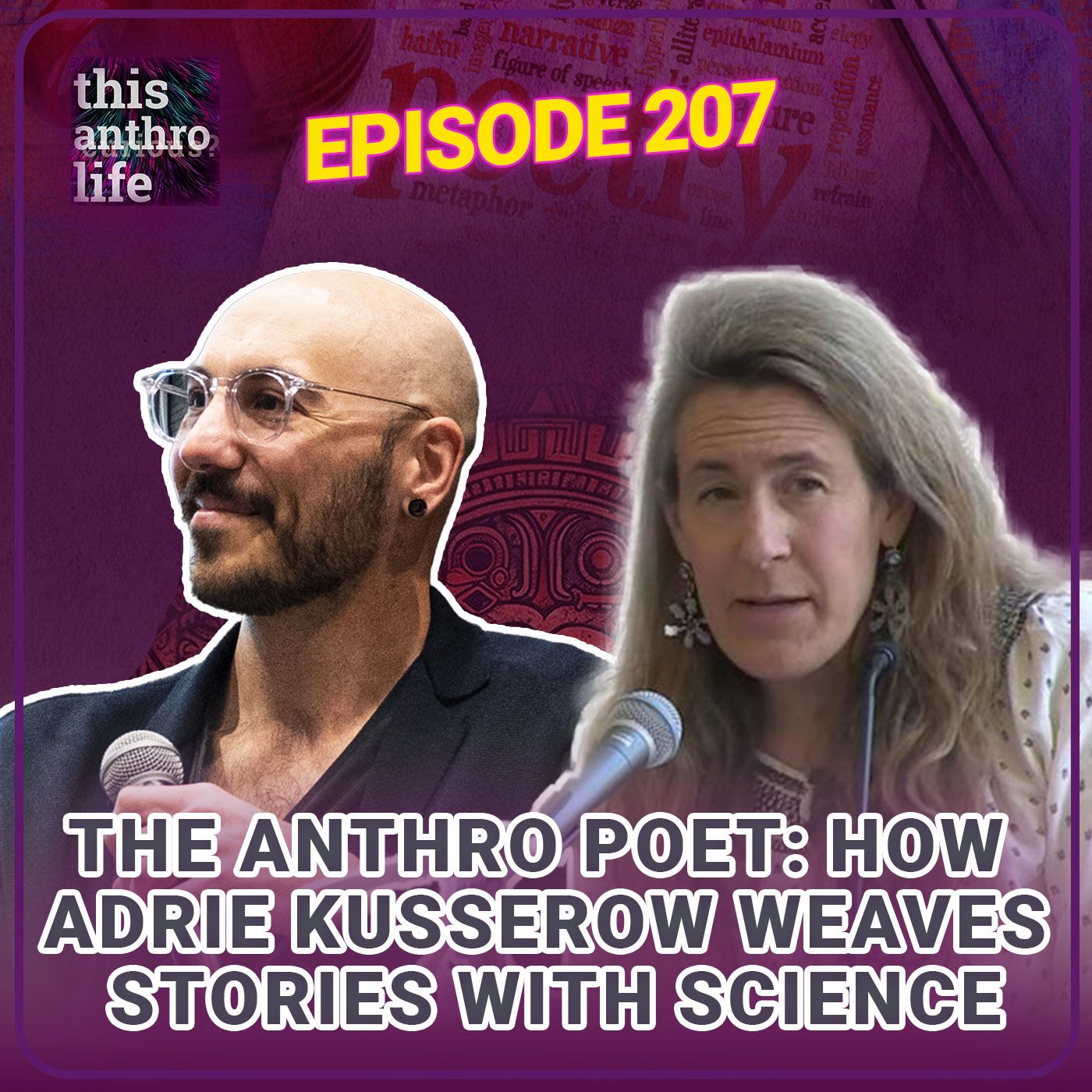

The Anthro Poet: How Adrie Kusserow Weaves Stories with Science

In this captivating episode of This Anthro Life, we engage with Adrie Kusserow, an esteemed anthropologist who brings a unique poetic perspective to her work. We delve into the essence of anthropology, emphasizing the transformative power of storytelling and its role in shaping cultural narratives. Adrie Kusserow shares her profound journey in Kathmandu, recounting how it shifted her worldview at a tender age. The conversation navigates through the intricacies of fieldwork, drawing parallels between anthropologists and refugees, and exploring the impact of language, emotion, and technology on cultural understanding. Adrie Kusserow's book, "The Trauma Mantras," becomes a focal point, highlighting the significance of authentic personal narratives in reshaping dominant discourses. The episode culminates in a reflection on the potency of poetry in anthropology and the ongoing endeavor to confront and redefine established narratives in a dynamic world. Join me in this enlightening conversation with anthropologist Adrie Kusserow as we explore the power of storytelling and the importance of engaging with different cultural perspectives. Discover how narratives shape our understanding of the world and how we can challenge dominant narratives to create a more inclusive society. Take advantage of this thought-provoking discussion.

How does poetry help us understand people better, using words that touch our hearts and reveal hidden feelings?

In this captivating episode of This Anthro Life, we engage with Adrie Kusserow, an esteemed anthropologist who brings a unique poetic perspective to her work. We delve into the essence of anthropology, emphasizing the transformative power of storytelling and its role in shaping cultural narratives. Adrie Kusserow shares her profound journey in Kathmandu, recounting how it shifted her worldview at a tender age. The conversation navigates through the intricacies of fieldwork, drawing parallels between anthropologists and refugees, and exploring the impact of language, emotion, and technology on cultural understanding. Adrie Kusserow's book, "The Trauma Mantras," becomes a focal point, highlighting the significance of authentic personal narratives in reshaping dominant discourses. The episode culminates in a reflection on the potency of poetry in anthropology and the ongoing endeavor to confront and redefine established narratives in a dynamic world. Join me in this enlightening conversation with anthropologist Adrie Kusserow as we explore the power of storytelling and the importance of engaging with different cultural perspectives. Discover how narratives shape our understanding of the world and how we can challenge dominant narratives to create a more inclusive society. Take advantage of this thought-provoking discussion.

Timestamps:

00:00 - Introduction to Adrie Kusserow and the Power of Anthropology

05:00 - Adrienne's Childhood and the Birth of an Anthropologist

10:00 - The Art of Writing and Engaging the Public in Anthropology

31:35 - Confronting Western Narratives of Depression and Individualism

35:00 - The Collective Nature of Suffering and Learning from Refugees

40:00 - Bhutan's Struggle with Western Influence and Youth Depression

44:30 - The Search for Authenticity and the Anthropologist's Role

50:00 - Language, Grammar, and Perception in the Anthropocene

55:00 - The Impact of Digital Communication on Emotional Depth

1:00:00 - The Interplay of Desire and Cultural Exchange in Bhutan

Key Takeaways:

- Anthropologists are like careful watchers of everyday people, learning from how they talk, move, and live to understand their lives.

- Refugees are like their own kind of observers, trying to understand a new culture and where they fit in it.

- Sharing stories is important for understanding pain, and different groups have different stories to explain what they go through.

- In understanding mental health and pain, Western medical ideas often take over, but we should listen to people's own stories.

- Poetry can help anthropologists explore feelings, experiences, and the small details of different cultures.

- How we speak and use language affects how we see the world, so it's important to pay attention to it.

About This Anthro Life This Anthro Life is a thought-provoking podcast that explores the human side of technology, culture, and business. Hosted by Adam Gamwell, we unravel fascinating narratives and connect them to the wider context of our lives. Tune in to https://thisanthrolife.org and subscribe to our Substack at https://thisanthrolife.substack.com for more captivating episodes and engaging content.

Connect with Adrie Kusserow

Website: https://www.adriekusserow.com/

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/kusserow-adrie-8a882ba

Twitter (X): https://twitter.com/mreddingtoncfi

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/adrie.kusserow/

Connect with This Anthro Life:

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/thisanthrolife/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/thisanthrolife

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/company/this-anthro-life-podcast/

This Anthro Life website: https://www.thisanthrolife.org/

Substack blog: https://thisanthrolife.substack.com

Adam 00:00

Welcome to the This Anthro Life. I'm your host Adam Gamwell. Today I'm thrilled to introduce our esteemed guest, Adrie Kusserow. A seasoned anthropologist who is illuminating work challenges conventional narratives and invites us into a deeper understanding through her poetic lens from feeling like an outsider after the passing of her father, to becoming a keen observer of normal people. Because hero's journey into anthropology is nothing short of profound. Today's conversation, we're gonna dive into the heart of anthropology, storytelling and the power of poetic expression. Because there are recounts her transformative experience at 19 in Katmandu, and how it reshaped her view of the world. We reflect on the immersive nature of fieldwork that draws anthropologists and refugees alike into the decoding of unfamiliar cultures. Now joining us as we discussed the importance of engaging the public through accessible and creative ethnographies the openness of graduate schools towards innovative approaches, and the responsibilities that come with our craft, we explore the intersections of language, emotion and technology. Considering how fast paced digital communication affects our ability to experience slow cooked emotions, like all aged casserole shares insights on the critical role of refugees, personal narratives that are often dismissed or contorted by dominant cultural narratives in western medicine, emphasizing the need for these stories to be heard and respected in their authentic form. So we tackle the challenging task of confronting and redefining narratives surrounding stress, depression, and the western model of the individualized self. And we dig into the global influence of Western biomedical discourses on diverse cultural understandings of mental health and suffering. Adrie has a great new book out called the trauma mantras that we're going to dive into and read some of the passages from, because it's written as a form of prose, poetry, it's a really, really wonderful mix. And so as you read some of these passages, we're gonna see that Adrie invites us to reconsider the impact of language on our connection to the world, and acknowledge the potential for systemic transformation in addressing things like climate change. And lastly, we'll dive into how poetry which is akin to music enhances anthropological fieldwork, analysis, and storytelling, enriching our sensory engagement, and questioning the Western medical approach to trauma. So tune in as we engage a conversation that promises to challenge inspire, and deepen your appreciation of the nuanced tapestry of human experiences. This is the center of life. Let's begin,

Adrie 02:11

I think I'm especially drawn to anthropology, because I've always felt like an outsider. And I think that that's something that started for sure, after I went through a very, very difficult period after my father was killed. And you know, again, I don't know if it's too early to dive right into a reading but but there is a piece that I have that that the day I really became an anthropologist, and it basically talks about how, in many ways, my response to that kind of tragedy was to look at, quote, normal people my age and study them, and try and imagine what it would be like to be inside their heads. And I didn't know that these would be later sort of anthropological techniques, frankly, that are, I would, I was practicing participant observation when I was nine years old, in that sense. So I think, in large part, and that has also, frankly, drawn me I you know, I love working with refugees, because I also think of refugees in so many ways as anthropologists themselves, in many ways, they're trying to decipher a new culture, I think of them is somewhat lonely, perhaps more vulnerable anthropologists, but to be with refugees is also to experience a culture for the first time, you know, when I walked down the aisle of a grocery store with a former lost boy, who looks at an entire aisle of cat food, and dog food and, and just can't get over this array of choices. It has that way of, of just, you know, you're seeing this from their perspective, which I think is tremendously liberating, at least for me, but so you know, I think the other thing which I can talk to you after about this is I ended up leaving college at 19 and going to Katmandu and that experience kind of introduced to me an entirely different culture. I had no idea. It existed. And from then on, my life was forever changed. I never looked at the world in the same way. And there was a certain high to that, in many ways, but if you want I'll read the first one of the pieces that is called the day I really became an anthropologist. Yeah, that'd be great. So This is based in under Hill center, Vermont where I grew up. I was nine years old, my father still a handsome, lanky Prussian God, when the 18 Wheeler crushed his green VW Bug. After that, I changed planets, and all was new and strange. Most days, I was dealing with the terrors of my body, the sudden sweating, the cut the crawl of koi prickled dread up my spine blossoming through my chest, the rocket blast of diarrhea, blouse drenched in sweat, rush to hide the shame. I knew I was a freak, but I had to survive on this planet. So I watched my classmates doing their human things nonchalantly eating their lunches, passing notes in class, I didn't like climbing around the cold sticky edges of my cave all fucked up and lonely like Gollum. So when I had to be conscious, emerging like a corpse from my valley and Benadryl haze, I tried my own version of participant observation, kickball at recess, hot lunches, Girl Scouts, bumpy bus rides and tag. I tried focus groups for girls giggling at an overnight. I hosted once a week, I studied them. I did whatever they did my sole mission to analyze their speech, tone, body language, smell rhythm, my own cells absorbing absorbing their logic. I built them with, sorry, absorbing their logic. I bait them with questions and watch the school of their rationales unwind. The ones they took as normal, natural. That's when I really became an anthropologist. When I can answer any question in the way they might, by ad libbing off their chill philosophy of life. The base layers even they weren't aware of. I called it burrowing sneaking inside the minds caves, viewing the landscape from their perspective. Strangely, it made me feel physically warm, I grew addicted to that feeling to the point where I'd space out in class participant observation, you plunk yourself in the middle of the bush in South Sudan, a high school in Bhutan and NGO and Darjeeling working and playing beside them. But simultaneously observing, when you catch yourself getting a little lopsided, too much getting lost in their world or too much standing aside and observing, you have to lean the other way. It's a delicate balance, I've spent my whole life perfecting, I'm not sure how I could ever turn it off.

Adam 08:08

And thank you for sharing. There's there's so much there, you know, it's like the even that last point of that we just can't turn it off, I think is a really powerful way to kind of in that piece too. Because it's there is this notion of you know, as one becomes an anthropologist, or just you have these moments in which I guess I'm thinking about this, like when I was doing fieldwork also as part of graduate school when I was living in southern Peru. But you know, regardless where anybody goes, right, like when you're doing you're doing fieldwork kind of outside oneself. And I remember having this distinct feeling of like, Can the anthropologist ever go home again, right in this notion of like, what where is home, right, because it's like, now you've been kind of in multiple places. And there's a kind of a rootlessness, but at the same time, I think what you you beautifully illustrate there too, is that there is something that hooks us into the ways that people live, right. And there's something about kind of finding almost a home. I also even think interestingly, how you also describe it as addicting to write of like, what it means to like, really want to get to know the answer without thinking about it. How someone is thinking, Yeah, I

Adrie 09:05

have to say when I hear you speak about, about fieldwork, it immediately really makes me think about the importance of an I think, frankly, the responsibility of anthropologists to write well, and, and to be totally honest, I also mean, right poetically. I do think that yeah, reality needs metaphor, rhythm, tone, description, generic words don't, don't truly kind of describe the habitus of a South Sudanese boxer. And, you know, I really believe that it is a responsibility for anthropologists to write well, and, and also to write in ways that engage the public with you know, frankly, The tentacles that stick to people. And a lot of times, for me, at least academic writing just slides right off and doesn't stick to me what anthropologists write about a lot of the time. It's, to me, it's it's crucial, important stuff. And we owe it to the world to give it a language. That is that's up to the task. I think. So, yeah,

Adam 10:30

I 100% agree with you. I mean, that that's the that point to it. So even I, the reason I even started podcasting, you know, in 10 years ago was, was in relation to this same idea that, you know, on the one hand, we find ourselves as students reading such interesting, fascinating accounts, doing fieldwork itself to writing and being in other places and learning, other ways of being in that there is such difficulty describing that right to different audiences, and even to the audience that we might be studying amongst, right. And for me, as a as a, I've come to accept a very slow reader, audio podcasting, speaking in video now as became a way to be able to how do we digest and then share the things that we're learning. And I agree to that writing as the most common way that anthropologists kind of share their work is your typical academic prose right is very difficult to read, for graduate students, let alone let alone a lay public, I think that's why your work is so interesting and profound and important is like, you know, through the trauma mentors, and the idea of like writing with this prose, poetic kind of format. And so I'm curious, like how you thought about crafting ethnographic thinking that way, you know, what made that format that way of writing

Adrie 11:42

kind of the choice that it wasn't, it wasn't necessarily a choice, it was that I found that I was incapable of writing too much academic. You know, for example, when I was in grad school, I was kind of sneaking undercover, I was taking poetry classes, I would never have told my, my social anthropology profs that that would never have been, or, you know, it wasn't like I was considering weaving this into a dissertation. When I was back then it wasn't, wasn't accepted, in many ways. And you know, I think I've I written in ethnography, I kind of got through grad school. But for me, it's not even a choice, I just find that what comes up in me is metaphor, rhythm tone, it's just much more of a kind of poetry when I need to talk about the the subtlety and the nuance of humans, I think, requires a certain poetic sensibility. So it's just what I kind of naturally gravitated for, towards, you know, and I think what's really interesting is that I don't use poetry as something that I might write 20, you know, 10 years after I finished fieldwork, for me, it's, it's become this interesting anthropological tool that I actually use to get closer to what I'm, it's sort of like a fierce meditation, that when I write about something, that very act of, of bringing poetry into my, my kind of analysis and thinking about something will give rise to other questions and other subtleties that I need to go back and check out. And it, I do think it, it enriches my analysis, although, you know, few would ever think of poetry as an ethnographic tool. But it lets me go into a depth of thick description in a way that ends up calling up so many other kinds of areas of question that make me go back and do the fieldwork. Again, and again and again. So it's not something I just tack on at the end, I use it right in the middle of fieldwork.

Adam 14:26

That's really that's really cool. I mean, that's, it's a that's definitely an uncommon or not spoken about kind of method skill, but I think that's really that's really nice. I like that idea too, because there's something I agree I feel an affinity with that idea where it's like it takes I'm a musician also. So, you know, some songwriter or have been in the past life, at least in in, you know, but I always remember the power of writing lyrics to have like, what does it mean to kind of put a story into a semblance of rhyme and tone, right and rhythm, and there's something that is, you know, obviously if there's music too, too, there's there's a way that makes you kind of remember It, like kind of feel it, I think in a more visceral way, and I think the same is true of poetry. And that's it, this interesting idea of like, can we how do we use writing in this way to process during into an analyze, to think, to raise to raise new questions. And that's, I think it's really compelling idea where it's like, if I'm trying to work through an idea that I'm seeing in the field, or even I think one of the really well in the book to talk about shortly is that you're talking about teaching students, right. And the challenge of that, and like, that was, to me also did this really good job of kind of hitting home with thinking about I taught for seven years, I don't teach now, but I did for a while. And just having this idea of like, thinking about being in the classroom, I'm working with students and having that I that's kind of like, I recognize those feelings, right? And these, like this kind of changing world around things like, around things like trigger warnings, yeah. And what we have to say and what we can and can't say in the classroom, and how we approach topics. And so, you know, but the idea of having something like, like poetry as a way to, on one hand, play with those ideas, right to kind of like, say, I need to bring them on to express them, but then also to be able to kind of play think through them as it were, seems seems really powerful. Yeah.

Adrie 16:04

Yeah. And it makes it forces you to engage with the senses. Smell touch. It's, it's, it's, that's what I love about it, too, is, you know, sometimes the senses are ignored a bit. And, yeah, poetry you just can't get away with ignoring all of the senses. I'm

Adam 16:26

wondering about so like, in terms of like, connecting that idea to one of the other like, big themes or character points that that is kind of throughout the trauma matrix is this question of the Eastern Western, like medical dichotomy, right? And then the, the DSM and the psychologizing, right, of every single kind of trauma or issue, right. And that's, it's making it very mental. And so I think to like, the, that kind of typical western biomedical model does tend to like de emotionalize things, right. And it's, it kind of makes everything very cerebral, and then it can be either like, processed through the head, or it has to, you know, somehow go through there to discuss it officially in air quotes. So I'm curious your thoughts about this in terms of like, do you do you see connection there in terms of like, if we want to kind of bust a few boundaries, as it were, you know, if we're questioning like a Western biomedical versus a different kind of model, even spirituality, I think also, another thing that I see it in the work to something about poetry helps us break that too, because it says, don't just think, but feel also, as we as we process this.

Adrie 17:23

Yeah, yeah. I mean, yeah, so so much of the book, I think, you know, it would be fair to say, I have this continual hunger to bust out of the confines of the, what I see as the, you know, the, the individualized, self and the often psychologize self. And I think that I think so many, I think another theme in the book is about stories and the ways in which we need stories to explain and understand our suffering, and we draw from cultural fabrics that are around us. And often, those are biomedical psychologize individualism. I don't know if you've ever read this book crazy, like us. It's by Ethan waters, the globalization of the American psyche, but he talks about how we draw from symptom pools that are legitimated and dominant and sort of the, you know, the water we swim in, so we don't even notice them. And I think one of the things that I love about refugees sometimes is that they come to this country. And the stories they have, aren't always necessarily the ones we want them to have to explain their suffering. It's fascinating how much I have seen as an anthropologist in terms of the medical system, wanting a refugee to explain their reality in terms of you know, biomedicine and through talk therapy, etc. There's a piece in the book that I wrote, actually, that's, that's called on the brilliance of your story. And it's about a refugee that comes here. And one of their stories is about, frankly, being a Jehovah's Witness. And that's considered denial by the doctors because it's not a psychologize story. And I think that there's sort of a hegemony of what stories we want refugees and people in general to weave about their suffering in this culture, and what ones we kind of looked down upon Yes, let's let's dive in. So this one is called on the brilliance of your story, and it's based in Burma, New Jersey and Vermont. And it starts with a definition of of something called psycho phobia, which is an aversion to psychological considerations your fingers still bruise your rosary with Mad devotion. When you first came to America, your loneliness swelling high above the bus station, up where the angels lay, you built your makeshift apocalyptic nest, pulling in the cheapest Jersey gods that flew around storm after storm in that neon grim city. Now you are losing it they say paranoid delusions of soldiers breaking into your house. You hide your car from the police clutching the hot vein of your cell phone as you drive your mother in her conical straw hat across the bumpy Vermont fields staring out from her Yoki all Alzheimer's haze as the car and lurches over the mud and leaves. I tell them to let you be let you suckle on the story that heals, even if it's one they don't approve. No one can weave as fiercely as you you who never should have been exiled from Burma. You afraid to leave your apartment now. The isolation you say now suits you, you and your tattered white bathrobe gray roots frosting your scalp peeking out from curtains to see who might be there. Like a spider sensing its web pricked, wrapping each social worker in the pure white gauze and clouds of Jesus's paradise as they look at you and speak to you of maintaining healthy boundaries, with the tenderness reserved for an infant or a dog once you recalled for them, the steamy jungles of your verse, the hell of your flight, where you ran and ran through the night and woke to a Python wrapped around a tree. Your father hacking its head off, prying it's 17 foot long body off the trunk. It took so long for it to die to uncoil enough so you could feast on the eggs lined up like potatoes in its womb. Though you tell them you are well that reincarnation landed you with Jesus. They say you are in denial of form of death of blindness. They talk to you of the dangers of psycho phobia. Show you a cartoon called quote my ego. What you really want to speak of is angels, the Holy Spirit, golden wings dappled light, the latest issue of the Watchtower for now who is to say what stories suffocate or heal which ones work or fall flat, which ones comfort us in the dark. The X rays of your brain with their gullies and Black King us may or may not save you. The stories they hear pearl to you for rescue can still let whole vats of plump suffering slide through their nets. As the white coats proudly drag you on to shore. The brilliance of your story they say is covering up the real story. Don't let them bit a little bit as you coax yourself home each night with the angels that calm you who is to say what holds you intact as your hurled through space, landing with a thump into the great American refugee hive and begin this frantic human work. Perpetual manic revival stretching your way through the half light of this vast unraveling strangeness

Adam 23:56

vast unraveling strange just makes me make the Think of how curious the Yeah, this the the space that we set up is I'm curious how the person that you wrote this about their experience here in terms of, you know, how they process this kind of space of being told that you know, you're you either have psycho phobia or you know, I chuckled at the watching a cartoon called my ego, you know, that kind of experience of of what was it like for them, you know, to kind of have to be told that we don't really want to talk about the Watchtower or Jesus or angels, but we didn't talk about the the, quote, trauma that you have. And when you go through that, like how was how did they do that? I

24:36

think what's interesting is so different refugees that I've worked with have either tried so hard to please, the doctors and the social workers that they're working with that they either give in and take it holy, it's pretty rare to be totally honest for many of the refugees I've worked with, too. pushback, it takes a lot of courage. You know, I've written about watching South Sudanese lost girls trying on stories about what they call stress, like stress and depression. So oftentimes I would go to the doctor's office with these girls. And the doctor would immediately ask them, Are you stressed? Are you depressed? And to them, this was that story, that way of explaining themselves was a ticket into acceptance into the culture they had to survive and make and do well in. And so I've seen, frankly, so many try, and almost like actors, practice these stories, and learn to get good at them. So that, you know, three years later, I'll hear this South Sudanese woman talking about her depressions with a casual illness, that tell that tells me it's taken root in a way that it didn't, at all, when she first landed here, but it took a certain amount of practice. So yeah, I guess it it really also depends on the rest of the refugee culture. And whether they, you know, I just finished teaching a book called The Spirit Catches You, you fall down. Yeah. And, you know, look at the model who are not taking on Western biomedical stories. They're continuing just to talk about the cosmos and, and poison liver, right, that's very different from, say, an Afghan refugee who's had a little bit of exposure to perhaps, you know, some, some of these more biomedic, alized individualized stories. So again, you know, I can't really say all refugees react the same way.

Adam 27:07

I think it's interesting, too, because like, because it seems also on the flip side that like this is also challenging, like good anthropology challenging the idea of a universal set of like an individualized self also, right, that that we tend to think is is the way that the being the self is in the western Yeah, kind of model. Right? You know, we have the Descartes tea and like mind body split idea, you know, which is funny, because even as that continually gets challenged by things like the gut brain access, you know, it's like, it still still hangs on is like, oh, there's a split between these two in oneself. And I think it's interesting to kind of, you know, give us pause to think, okay, it doesn't mean that somebody can't feel stress, like there may be a cortisol spike in their body. Yeah, when something bad happens. But when we define stress, like it's experienced differently, right, or people may kind of talk about our depression to that it's not just this one blanket thing that has a strict biometric. I think

27:58

it's very interesting to how, you know, and it's not to say they don't experience stress, but the first impulse for, you know, a Sri Lankan Buddhist might be, of course, we're stressing the social fabric, and not even think of placing into the individualized body. Or maybe we're stressing the creation myth, or challenging or soul loss or, you know, so I think, again, just the automatic placing of it within the confines of one body is, is pretty rare, globally. But that said, I think we are we are globalizing, like Coca Cola and McDonald's, we are definitely quickly exporting Western middle class conceptions of self and mind and body all over the world. And, yeah, yeah. And

Adam 29:01

it's a challenge, right? Is there like, because I'm thinking about this on the on the sort of coming to the US side, also, you know, there's obviously, yoga is a very common practice that a lot of people do like, but it's been very westernized, right, as the former practice, we may think about in a studio wearing spandex and having your foam bricks to stand on, you know, well, a nice form of exercise, that's very different from kind of yogic practice that we would see in Central and South Asia, right. And this interesting idea there too, of like, how other practices also get subsumed kind of into our individualized model of self. Here's this interesting question of that. Like, it's, it's one of those things that makes me uncomfortable to think about like, if we have a hegemony hegemony going out and one coming in that like it's a filter that that kind of says everything functions this way, because I don't want to give the dominant you know, power paradigm to this way of being you know, I guess, do you see cracks of that, you know, like, does there kind of ways of like it doesn't, we are exporting it, but it doesn't just like lands at wholesale. Now we're all individualized, but it's intriguing to see how that that filters like I guess I'm just I'm one You're gonna hopefully that also more individualized or more collective senses can also find their way into western models to, you know, through through either refugee or otherwise cultural interaction, you know, I guess do you do kind of see there? How do you how do you? Well, I

Adrie 30:13

will say I've been, as a, you know, psychological medical anthropologist, I've seen so many more studies on the degree to which cultures have been kind of mowed over and replaced with biomedical discourses. So, for example, you know, this idea that, that of serotonin and the broken brain and, you know, kind of the Prozac II and explanation about sadness is this is a serotonin deficit. And I think that's been shipped around the world, in many ways, thinking that would liberate people, in a sense, because great, you know, I just have a serotonin deficit. And as it turns out, the broken brain metaphor, frankly, has left many people who have since, you know, say shifted from thinking it was a spirit possession, to a broken brain thinking it's a permanent problem that cannot be fixed, and made them worse. But there are studies coming out, I just just looked at a study that was wonderful about this community in Belize, that wasn't succumbing to anorexia, and, you know, television, it's is often kind of seen, I think, as a can be a cause of a rise in eating disorders. And this one place has a certain ethno conception of the self that basically says, No, we're not taking that we're not, we're not going there. We're not we're just we're, we're, we're gonna stick with what we've got. And we're not going to buy into that. But I think I'd love to see more studies that show these places that are successfully doing that, I think we could learn a lot from those studies.

Adam 32:14

Yeah, no, that's a really, that's fascinating to it, because it is an interesting point of, you know, how we tell those stories of how an issue like depression or sadness happens or and when we individualize it, you know, it like, you know, the the other side of that, of course, is that we, we basically say that it is not collective, nor is it something beyond just the individual body. And, like in the Depression is a great example, though, to where it's like, you know, we've seen We've seen also medical studies kind of that show that when you're just treating serotonin, you know it on some levels, like your your, what is it your dependence of it can go up, if you need to have something like a Prozac or fluoxetine because then your your body metabolizes it faster. But the thing is, it doesn't ultimately solve the underlying issue, oftentimes, right, it kind of like, covers it up in one hand. And the funny thing is to like, the other simple things like exercise, and being able and being able to socialize, you know, I'm not, I'm not gonna diminish the challenge of doing those when one feels incredibly depressed. But doing those activities, you know, also can have a huge impact on how one feels, you know, the inertia to be able to do this is one of the hurdles there. But the interesting part to that, like both the idea of moving body and then also being with other bodies can have incredibly ameliorative effects of most of many things, right? And that interesting idea of like, when you because when we also put it on the individual body, if you think about it, too, that the way that we might internalize that, perhaps makes it even harder to then get the inertia up to do something. Yeah, to be able to move, I think, and that's it's interesting point. Yeah, the

Adrie 33:37

idea that the I really believe that suffering, if you know that suffering is something that everyone else on the earth is going through, that it truly does wind around and have an impact on your level of suffering. Whereas if you think I am this strange, whacked out freak, the only one who's going through this, I mean, what what I really do believe, you know, one of the things I teach in my refugee health classes, why are Tibetan Buddhists, such adaptive refugees, in large part, you know, you have to ask yourself, what How would it feel to take one suffering and also give it the story of this is making me a, perhaps a better Buddhist, it's allowing me to empathize. It's allowing me to reduce karmic debt, you know, so I really do believe that the stories we tell about suffering, they end up looping back and raising or lowering some of the the brutal experience of that suffering. So I think we have a lot to learn, frankly, from, you know, refugees like Tibetan refugees.

Adam 34:57

Yeah, that's a fascinating point. And I love that idea that But when we understand how the stories we tell, shape our perception and ultimately how we experience things, we realize just the power of that. Right. And like the the other, I think liberating piece of that, too, is that we hopefully in that can recognize that we have the ability to tell other stories, right. And one that there are other stories, right, we have Tibetan Buddhist, that are telling a different story of suffering in refugees in this context, and that we might also tell different stories in that way, let alone learn from other people's right. And I think, again, it kind of also points just the challenge of when we have this such an individualized model, it's that it's that we then think the story is somebody else's story, right. And we see it as that only right without realizing that this could be my story too. Right? There's, there's something about that. And that's, I mean, why humans are a storytelling species, right? Like this is how we make meaning is that we tell each other stories in this way. And then it's interesting that like, some things, I mean, I guess the idea of a story, right? In and much of our western mindset, yeah, it's a fiction. It's a fiction, right? We think about I mean, we have to say nonfiction story, right? We think story is somehow not true. And that's interesting when you realize, but like, how we talked about IP oppression in environmental context, I do think, like, I mean,

Adrie 36:06

one of the things that I also write about is this, you know, fictions of East and West and how we feed on those fictions. And, you know, I've definitely noticed with refugees who are resettled here, oftentimes and attempt to post on social media fictions of their, of an idealized life here, that gets eaten up, back home, and interpreted as everyone's happy over there, which makes people more miserable in the camp. So you find oftentimes these these fictions that occur that can be pretty harmful to quote each side.

Adam 36:50

I think that that's a great point. Yeah, it's I

Adrie 36:53

experienced this in Bhutan. So one of the, the things I've done in the past for fieldwork has been with this Bhutan Center for Media and Democracy. And I worked with youth from rural Himalayan areas who were basically experiencing social media for the first time. And I was completely blown away by first of all, what they thought of the US as a land of complete happiness, and, you know, all sorts of other idealized images of the West. But you know, so what was fascinating about being in the capital timbu, in Bhutan was you had these Westerners coming there, because they wanted this spiritual kernel that they felt existed indigenously amongst the Bhutanese. And yet, there's an incredibly high rate of drug addiction and depression among use in the capital of Bhutan, because I think they all are getting this feeling that they're, you know, that they, they need to be more Western, they want to get off their farms and not smell like manure, and they're watching TV shows about urban life with gangs. And so they come to timbu. You know, they come to timbu and they think I want to be a city person with a fancy desk job. And lo and behold, there aren't any jobs and they get drug addicted, and then they're completely lost. So anyway, this one, I can read this, it's called Bhutan East wants West and wants East. And this is Tim fu Bhutan. I'm back again working for the government in the last country on planet Earth to get internet. Here to preach the dangers of Facebook, Instagram, Tik Tok, the sexy fiction's global media spins about the West. The government calls it selective modernization, letting in only the best of the West, but all I see are guns, gangs and actors bleached in Fair and Lovely on the tiny TVs now in every store on this street. They tried banning MTV World Wrestling Federation Fashion TV, but now the flow is impossible to stop the channels breeding and multiplying. Even among the farmers far outside the city satellite dishes caulk their chin South magnets to the subtle, Sly presence of envy, creeping into houses like stray cats coyly rubbing and curling around their hearts. Each day I walk to the top of the Tim Poole hills where the sun leaves it's after bursts everywhere. prayer flags drench the Pines a monk scampers away like a red fox, couples park their cars, condom wrappers are lodged doggedly in the mud, asserting their rightful place in the path to enlightenment. dingy Indian buses painted gaudy as prostitutes careening around the battered road to the capital, taking villagers to Tim Fu, where among youth lust for the West huddles like fog packs of roaming boys dressed in black jeans and T shirts. Scout the streets for drugs. The ones who are the Westerners hungrily black eyes nibbling feverishly at the manic commercials flashing from the store front TVs. These are the boys who fail their exams left their farms mocking their prune faced grandparents huddled in dark corners mumbling mantras. They want computers not soil, Bollywood, not Buddhism. Now they sit hung over at the dingy Youth Center. Unemployed faces pinfold and tired confessing their shame to the Welsh monk who has made it his life to help them gutted and global the wet viscera of shame leaking from them. He sits patiently in his faded burgundy robes trying to bring them back into the fold. Meanwhile, tucked above the cobbled streets in the smoky timbu Disco at the own bar, CNN shouts its noble manifesto from its perch above the liquor, schools of ghostly European expats sway weaving their drunken limbs lightheaded, won from this geography of bliss, geography of want the Bhutanese boys snorting coke in the bathroom, emerging in black leather jackets and slicked up slicked back hair, going straight for the Western girl who looks like Britney Spears. After their tracks yoga or meditation. The Westerners lay their drunken bodies down on the stiff hotel beds, were all night they try and meditate, let it go, let it go. And still they come back to this density of longing, hard kernel of desire where the bulky psyche chips its tooth, and winces again, stumbling back to the breath, outside my window, deep in the alley below, the Bhutanese boy high on meth wailing a kind of love song for the West while barking dogs mince the night to let bleeds.

Adam 43:02

That's a good piece, I think this idea of this geography of logging of this this kind of like anatomy of always wanting the other sunsets or trying to like always capture it and like how in this case you you both capture right this kind of very concrete hard Visser ality of like a leather jacket and snorting coke and like becoming drug addicted. And then also this idea of the the Westerner on their yoga retreat, laying down and trying to capture that breath that just seems to keep getting away from them also as the thing to focus on. And this is happening in this in the same place. You know, I think that's it's a powerful reminder too, that like where we see this, both desire for crossing and that like it's a kind of as you as you know, to like kind of cuts both ways, right, that it's not just one pure export, but we really do this interesting mixing there, right this this interconnectivity that we don't realize, like, we're we're all chasing as simulacra. Right? We think something else is,

Adrie 43:52

and I will say I would include myself in that Western nomadic tribe of one of my worries is that I come across as if I'm somehow beyond this, or I'm very, very much one of those people who has scoured the east, in many ways, as a teenager trying to find a more spiritual, you know, kind of axis authenticity, etcetera. I'm very much one of them. So authenticity,

Adam 44:26

yeah. Yeah. Yeah. Like in to your credit to like, you talked about that book, often to like you, as a character in there are questioning and knowing Okay, I did this, you know, and I think that's important too, right? That like, on the one hand, it's the the anthropologist self reflexive turn right of saying, I know, I'm part of the story, and I'm shaping what's being told. But also I think it is that itself is also more authentic, right? Because it's like recognizing that we are anthropologists never outside of the world with the system, right, that we are, we are ourselves. I think a lot of us are seekers in the sense of trying to find something more authentic, more real, but then we realized that Oftentimes, it's always in these hybrid spaces, which is never perfectly comfortable. But, you know, but we have to have our story as part of that. Because otherwise, then we are kind of talking about as this distance observer doesn't exist, right. Yeah, you know, which is important to recognize that we're part of it. I'm thinking, I wonder if one last one, I'd love you to read that. I think it's really interesting too, as a way for us to maybe even kind of wrap some of these thoughts is the trouble with the with Anthropocene grammar. And it's a piece that comes towards the end, because what's really powerful is it's a meditation on language. I think somebody else to help us think of it as we've been talking across the idea of like, how, you know, on the one hand, like trauma and suffering may be experienced, but like the way that we tell those stories can make us feel more connected or more isolated, in the way that we also seeing desire kind of passed, you know, in across borders, even as we're seeking for something that's that's quote unquote, more real. And I think this key point to that language plays a role in what this this can look like for us as well. So I will stop talking about it. And let's check it out. This

Adrie 45:57

it's called you're exactly right, the trouble with Anthropocene grammar, and it starts with a quote by Mark Dodi who wrote the art of description. And it is the the quote is what is description after all, but encoded desire when my son was barely a year, and he poked his head up out of the crib, all warm and yeasty hair stuck up like two soft horns, beaming brighter than a headlight in anticipation of the nip. That's when I noticed at most, a bubbling up of adjectives of fierce cooing, rapid fire of tiny love names. Tender pink, niblet, luscious little beast, water nut, love blossom. Latin became the cheap toy. I marveled at the service of my desire. Pontus Barbossa luck Tada nippy Jana Pincus Shabbos hummus even as a child as I walked the woods and came across an orange spotted Nuit owl or deer, a kind of verbal fever. A love smitten Tourette's rose, my brain wild with metaphor, swinging from branch to branch of simile. Trying to match the newts succulence, it's adorable toddler waddle across the damp black soil. Or in June the pink veined pouches of the lady slipper, both ephemeral and genital floating Toad balloons, half scrotum, half fairy, walking the woods I was a sound Nim tickling the moss with alliteration, a Swedish Mazouz, rubbing the mushrooms with vowels. Now my students are learning about the ways language and grammar shape how we think and perceive. I tell them, they come from a noun heavy culture. I'd rather be from a verb heavy, heavy one that acknowledges the vital beingness of our world. Here we start them young at the noun factory, the naming of everything. This is a dog. This is an apple, chicken, pencil, cloud, son, we point and point and when they get it, right, we praise we love to separate atomize we are reading about the Potawatomi language. And I can tell the students are hungry to experience nouns as verbs. To be a hill to be read, to be a bay to be Saturday. A hill is a noun only if grass is dead. I can tell they are intrigued. Rocks, drums, apples, fields, fire. Even stories are allowed to bust down the doors of this strict human alive. Slash thing, dead dichotomy they were raised on. Just try to be aware, I say, of how our grammar corrals us into giving a subject for every verb. So we say it rains or the light flashes when neither one can exist without the action itself. Nor do we even note mere gradations of animacy, lawnmowers, malls, peaches, soccer balls, iPhones and hummingbirds are all referred to as it I tell them our grammar makes it hard for us to understand Albert Einstein's theory of relativity, but easy for us. To get the linear logic of Isaac Newton's chunky objects bumping against each other, easy for us to know when we are late to class by one minute and 30 seconds, but hard for us to smell the urine of a monkey a mile away. I scan the classroom. One student looks crestfallen, as if she's been sentenced to a dead end world. None of them have thought about the relationship between the grammar our European ancestors passed down and the climate change that looms before them, I want to give them hope. So I tell them, even though we are now in heavy subject, verb dichotomous, we can still listen to the bubbling that rises inside us when we sense something's animacy even though our language calls it, it, our hunter gatherer bodies are still designed to vibrate when close to another's animacy the frenetic hum and bubbling of the urge to describe a tulip, peach, Wild Rose mountain or Fox before the next text comes in. So perhaps for climate change, we need to create space for giddy language to rise up in an intoxicating effervescence. A dizzy, almost Bewitched, speaking in tongues, a space to let the endless metaphors the vows broken, open, bowled over with awe burst force landing and re landing on what you are adoring, in some guttural visceral way. It is the doggedness of the adjectives as they crowd your mind, our species determination to match the infinite animacy of this world that will make it harder to destroy.

Adam 52:04

Yeah, I really, I really liked that piece. What is really sitting with me too, is even thinking about, you know, we're talking about poetry at the, at the top of the conversation too, and just this need an ability to use language in a multifaceted kinds of ways, right? And like one of them, especially when it comes to anthropology or this like, you know, it's funny, because you're describing a classroom scenario, which like are discussing, you know, Sapir Whorf hypothesis in like, you know, linguistics, right. But then doing this in a way that is like, the way you write it here. And then kind of in recited to is like, it's a very poetic experience, right? And recognizing, I think in all of us, we said, One Mind blown that I realized that language is shaping how I see the world, but then secondarily, oh, wait, I don't like now what it's now I've realized what this is defining. So what do I do with that? You know, and, you know, seeing that there are other ways of telling those stories, but then also even even the way that you kind of render this, I think there's, there's such value in like, both how we think about teaching, right? And so that's why I appreciate this, this piece, but then also recognizing that, like, I'll make a lot of us do feel, especially if we hear something like this, that kind of language that we use really shapes our our perception of the world, right? And that we longed for that sense of intimacy to with a sense of aliveness. Yes. And, and when we feel it, we know it, right? And oftentimes it can't. And the funny thing, too, is when you realize when you can't explain it, when you kind of felt something that doesn't quite have words, yes, like limit experiences of Michael Jackson, the anthropologist, you know, talks about that, that these notions like that the birth of a child or death of a parent, like it's hard to describe what that feeling is in that space. But we feel I definitely think

Adrie 53:31

we, we feel it, but the iPhone phenomena, I think has, it also has created a sense in which we feel something but then a text comes racing in and we don't get a chance to develop what I think of a slow cook kind of emotions like that are ironically, so important for our world. You know, one of the things I think about a lot is, is the ways in which, you know, technological stimulation, if it's constant is very much shaping the kinds of feelings we have on a daily basis. To what extent does does Ah, really get a full chance to unfurl? We're really good at anger, laughter, judgment. We're good at these quick flex feelings. And I think we need to keep holding out spaces and room for these feelings that frankly, take a little longer to unfurl, but are nonetheless still so important.

Adam 54:44

Yeah. I mean, it's it's that's really wonderfully said and I, I agree, because it's like, because the feeling is fast does not make it more valuable, right. Efficiency in this in this context does not equate value, right in terms of efficiency of calories spent to feel, you know, but yeah, I think that That's a that's a great point to that, like the end, even as you're, you know, in the piece to write that when the text keeps coming in, it continually disrupts a slower feeling that takes more time to be felt. I think that's, that's, I mean, that's a that's a profound piece of advice for us to think about. It's how do we create, and continually nurture those spaces that give us more room to feel? How

Adrie 55:18

do we not place it again, our bias is to place the responsibility of creating those spaces on the individual. And to be upset when a teenager cannot create that space successfully. How can we create, you know, mandates in public institutions, for example, that say, from 12 to one, you can't be on your phone, it's not allowed or something. Again, I just see the very quickly locating all the responsibility within the individual. And I think that's, that's too bad. Yeah,

Adam 55:57

right. Yeah. No, thank you. Right. And that's an important point, because I'm reflecting on, I've done a number of different jobs over the years, but I worked in corporate research for a little while, and even even how we like talk to market researchers, right, there is this idea that, like, we have to help the consumer, which is the individual, right, it's never like, you know, it's very slowly some companies are starting to say, there's, there's families, there's groups of people, like the family is the closest nuclear unit that we get, you know, and that's, we have, you know, very much from Yeah, Margaret Thatcher and neoliberalism, you know, but but like, beyond that, it's like, how do we actually like you, right? Like, say, it's not just the individual or even just the family, right? But it's actually we are social units that are bigger, and like, what does it mean to have like, imagine if there was like, again, mandatory always sounds like a negative thing for you know, in the American quote, unquote, Freedom context, but like, imagine if we had like, mandated meet your neighbor day, you know, that sounds pretty nice, you know, just these ideas of like, yeah, like, what does it mean to have those spaces of like, tech down and put people up, you know, in spend time with? Yeah, yeah, I think in the inside, we know that these are possible. I mean, I'm saying this as a as a as a, you know, is that we all seek seek for different kinds of things, right. Oftentimes, burner, you know, from Burning Man and regional burning events to in part because they are a intentional community building that they're like, their artistic expression, but like, a lot of it is about like, how do we spend time intentionally together? And, and, you know, just that simple fact, is like, a renewal, sense of like, you know, and we know, we have this capacity that schools can do, or they can be space for that they can be space for that in community centers, religious centers. So I think it is a really interesting question of like, how do we how do we think about that as a public good, right, to kind of offer this this kind of space? I think that that's, yeah, I'm coming away from this thinking about this question.

Adrie 57:35

I read this book called rewire, rewire by Ethan Zuckerman. And it was remarkable in the way, it made me realize how much we get in grooves and habitual patterns of just checking out for things on the inner net every time every day. And given what the internet is capable of doing in terms of expanding our levels of or really, you know, perhaps learning about another culture. What sad, I think, is that, again, we're just we just get in these train tracks where we check the same old thing every day. And we need sort of people who can tell us, you know, hey, jump out of this for a second and go to this other place, and it'll expand you in ways you never, never occurred to you, you know, so we end up staying with the same wisdom of the same flock in our little grooves. And I think we need people to help us jump out of those groups, you know,

Adam 58:39

yeah, that's a great, great point. And it's like, you know, you know, the end sample size of two here, but I think our biases, anthropologist, and social scientists are particularly good at doing that. Because if we just say, let's actually pause and ask the question, Do other people do this differently? Like, or what might this look like if we think about the relationship of our words with how we think about the intimacy or not of everything around us? And so I think I mean, to come back to the point you said, up top to right, that I think I think I agree that anthropology has a responsibility to be able to help help those kinds of moments take place, too, right? And so also why I appreciate your work in that, like, you know, how can we also put out writing ideas thinking that that are accessible in different ways, right, because it gives us not just an academic treatise, or dissertation that nobody literally can read? Because blocked me on a university paywall, but like, also, you know, the idea of like, of prose, poetry, so I'm inspired to kind of think about writing this way, this way now, too, because I think it's a really nice way of like, it's not, it's not intimidating to have to get to write a chapter. It's like, you need to write the idea. Right? And you need to feel the idea like that. That's a really nice way also, because even this, I mean, speaking of groups, if you're admitting I'm thinking about one, right, it's like, we think we have to write in this specific 10 to 25, page chapter, whatever, you know, that it is versus like, well, actually, no, let's get the idea out. Yes, yes. And then go from there instead. Yeah. And I think

Adrie 59:51

we are getting more and more grad schools that are open to this kind of creative offense. You know, our Artspace ethnographies that are using Art and Writing and music to open up ethnography, frankly,

Adam 1:00:09

awesome AG, I just want to say thank you so much for joining me on the podcast. This has been great to talk with you and into here, you know you read different pieces of the book. I'm excited for folks to check it out as well. So just thank you so much for the work that you're doing. And it's been great to talk with you. As the echoes of our in depth conversation began to settle, we draw the curtains on another enriching episode of This Anthro Life. Today, I've had the privilege of exploring the rich tapestry of the human experience with the insightful and politically minded anthropologist Adrian Cicero. We've delved into the world of refugees, the nuances of narrative and the deeply personal quest for understanding within the tapestry of cultural perspectives. Adri has eliminated the path by stressing the importance of not just studying the world, but truly engaging with it. Through the poetic prose of anthropology. Her powerful storytelling and devotion to crafting stories that resonate beyond academic circles have left an indelible mark on anyone who seeks to understand the complex narratives of our shared humanity. So I want to extend my heartfelt thanks to Adria for her enlightening contribution and for reminding all of us that there's a profound beauty in the stories that we tell in the experiences that we share. So to you, our dedicated listeners, I pose a question that might stir your reflections on this episode as well. What are the stories that you've heard, or perhaps the ones that you've lived challenge the dominant narratives that shape our lives? What lessons can be learned from embracing these variances and the human saga? So I invite you to ponder on this and contribute your thoughts to our ongoing conversation. In today's topic of storytelling and narrative anthropology has piqued your interest. I highly recommend Adri customers published works, which you can find in our tale bookstore link. And of course, set aside a moment to visit our Anthro curious substack blog for more engaging content and discussion. And your voice is an essential addition to our community narrative. So contributions and curiosities are always welcome. So please do in fact, reach out in today's episode resonated with you please share the inspiration by sharing it with someone that you know will appreciate the wisdom that we've unpacked. And of course, don't forget to subscribe to this afterlife for a journey into new human horizons. Engage and share your feedback and let's embrace our role and the intricate mosaic of the human experience and until our paths crossed again in the next episode, stay thoughtful, be bold in your explorations of life's narratives, and as always remain Anthro curious, I'm your host Adam Gamwell bring you a fond farewell for now. This is the central life where every story every voice matters.